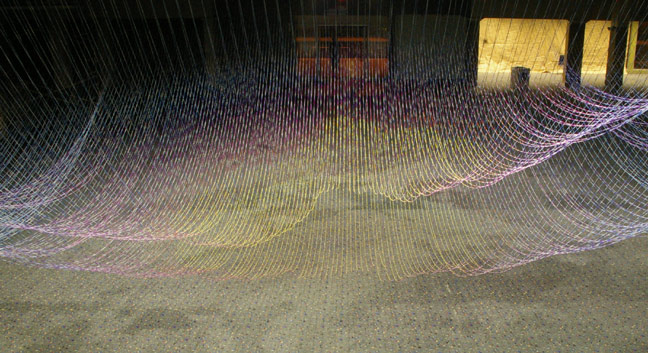

When entering the voluminous open space of the first floor one is immediately struck by the monumental yet airy site-specific installation by the Ball-Nogues Studio. An architectural firm, the Ball-Nogues Studio is known for their large “structures” of painted string, called Suspensions, of which another smaller version is currently on display at MOCA’s Pacific Design Center. Multi-colored string is suspended from the ceiling to create huge waves which undulate as one moves around the piece. Light bounces off the multiple colors, radiating differing effervescent glows depending on the viewer’s perspective. The piece masterfully mixes handicraft with digital design. The string connotes traditional needlework, yet the piece is conceptualized using computer software and a special machine designed by the Ball-Nogues studio creates the variegated string.

The overall effect is an overwhelming sensory experience that seeks to challenge notions of the temporality of imposing structures. As co-creator Gaston Nogues explained in an interview, “We think this has implications for architecture, approaches to thinking about architecture that are more unconventional. I mean what is really a building? Does it have to be made with drywall and be there forever? We’re trying to challenge those ideas.” Stretching the boundaries of architectural practice, Suspension is awe-inspiring in its translucence, ephemerality and complexity.

My favorite piece of the evening is an enchanting installation by artist and set-designer Melissa Ficociello. Ficociello transformed an upstairs room of the building into the site of a mythic western fairy tale by covering the floor with gravel (which loudly crunches under the visitors’ shoes) and tying dozens of hanging tumbleweeds to the ceiling. A lone spotlighted chair is placed in the center of the room, vaguely recalling the space’s original purpose of furniture sales. The walls are left untouched with varying splotchy paint colors and visible infrastructure (presumably from unfinished restoration) all of which help to emit a sense of decaying industry. Combined with the tumbleweeds and the unexpected pebbles under one’s feet, the room projects an otherworldly feel, as though it has been overtaken by a deserted garden in an alien landscape. The installation provides a fresh and peaceful experience which is wholly disconnected from the hubbub of the surrounding video art, much of which seems randomly placed and rather repetitious.

Another absorbing installation is “Nestation”, located in a downstairs nook that may have been a furniture salesman's office in the building’s previous incarnation. The work is part of a series entitled Beau Monde Float Thirteen-Six Views of Sound Beauty and was designed by Marco Schindelmann and Karen Cruise with the collaboration of Hope University, a daytime program for developmentally disabled adult artists. Schindelmann and Cruise transformed the room into a nest overflowing with branches, long multi-colored crocheted tubes and other nest-like objects. Throughout the evening gallery-goers would themselves nest, enjoying a glass of wine and conversation while sitting in this oversized human-scaled roost. The work is intended to explore varying notions of beauty, aesthetic prejudice, and the role of environment in human development. Speaking with the artist (who I found perched in the nest knitting) the role of the marginalization of the developmentally disabled was a profound source of inspiration. In an interview Schindelmann explained that

various communities create the equivalence of nests, and nests are really environments in which certain trait sets are perpetuated and so within nests even though you do have nurturing you also have competition, you have exclusion. The developmentally disabled community is a marginalized community although twentieth century art was very much informed by such communities, aesthetically speaking. We decided to show the exhibition space as a microcosm of what occurs within the nest as well.By itself, the work does not clearly articulate this position. On the contrary, I found the piece to be comforting rather than restrictive, a site of nostalgic childhood fantasy rather than a cutting critique of art world exclusion.

Despite its lack of a cohesive theme and video art which mostly falls flat, “Long Beach Exposed” is a successful show made up of a talented group of artists who have created immersive installations which transport the gallery-goer through sensorially transformative pieces.